Let's Encrypt's New Root and Intermediate Certificates

On Thursday, September 3rd, 2020, Let’s Encrypt issued six new certificates: one root, four intermediates, and one cross-sign. These new certificates are part of our larger plan to improve privacy on the web, by making ECDSA end-entity certificates widely available, and by making certificates smaller.

Given that we issue 1.5 million certificates every day, what makes these ones special? Why did we issue them? How did we issue them? Let’s answer these questions, and in the process take a tour of how Certificate Authorities think and work.

The Backstory

Every publicly-trusted Certificate Authority (such as Let’s Encrypt) has at least one root certificate which is incorporated into various browser and OS vendors’ (e.g. Mozilla, Google) trusted root stores. This is what allows users who receive a certificate from a website to confirm that the certificate was issued by an organization that their browser trusts. But root certificates, by virtue of their widespread trust and long lives, must have their corresponding private key carefully protected and stored offline, and therefore can’t be used to sign things all the time. So every Certificate Authority (CA) also has some number of “intermediates”, certificates which are able to issue additional certificates but are not roots, which they use for day-to-day issuance.

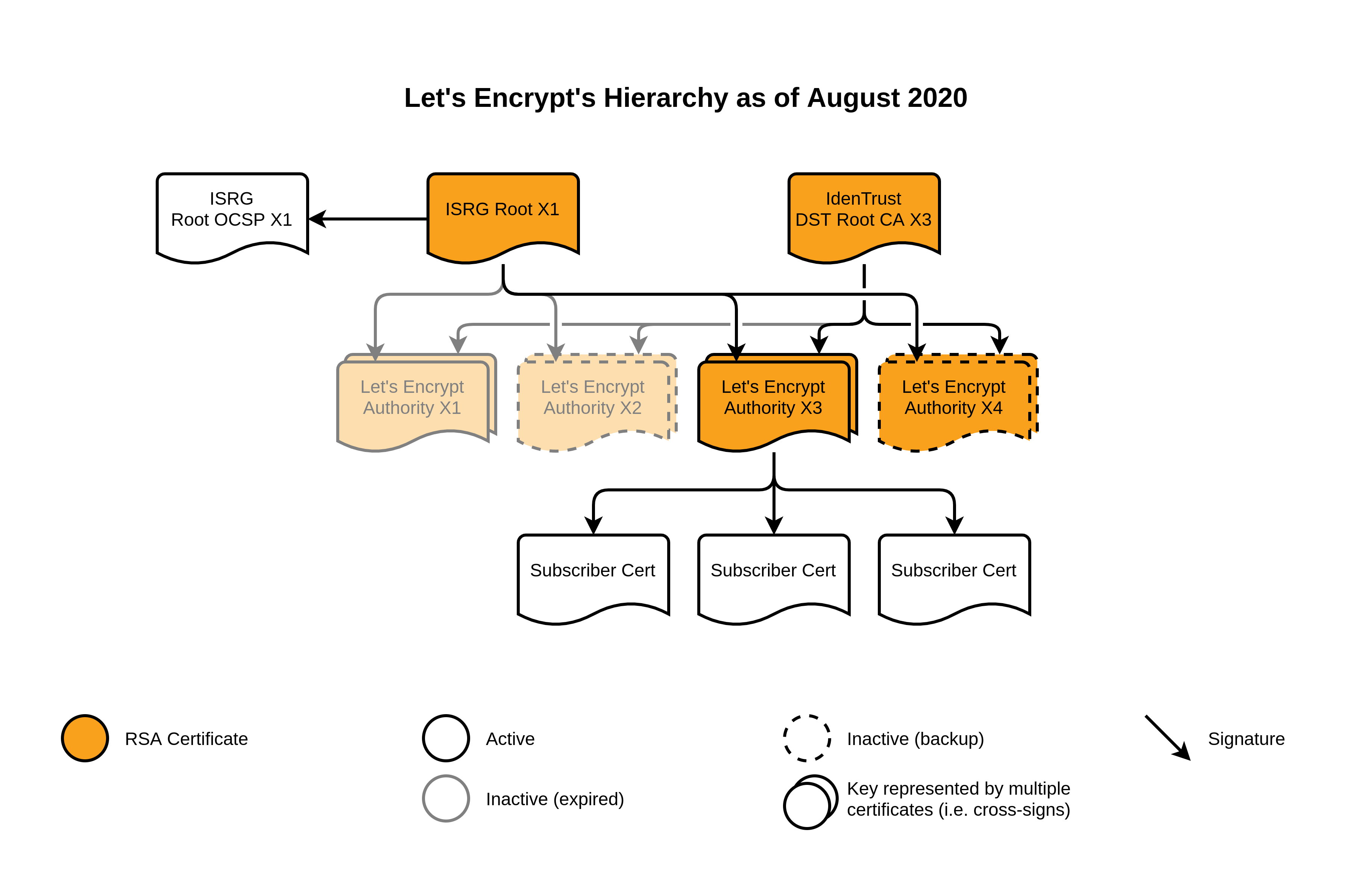

For the last five years, Let’s Encrypt has had one root: the ISRG Root X1, which has a 4096-bit RSA key and is valid until 2035.

Over that same time, we’ve had four intermediates: the Let’s Encrypt Authorities X1, X2, X3, and X4. The first two were issued when Let’s Encrypt first began operations in 2015, and were valid for 5 years. The latter two were issued about a year later, in 2016, and are also valid for 5 years, expiring about this time next year. All of these intermediates use 2048-bit RSA keys. In addition, all of these intermediates are cross-signed by IdenTrust’s DST Root CA X3, another root certificate controlled by a different certificate authority which is trusted by most root stores.

Finally, we also have the ISRG Root OCSP X1 certificate. This one is a little different – it doesn’t issue any certificates. Instead, it signs Online Certificate Status Protocol (OCSP) responses that indicate the intermediate certificates have not been revoked. This is important because the only other thing capable of signing such statements is our root itself, and as mentioned above, the root needs to stay offline and safely secured.

The New Certificates

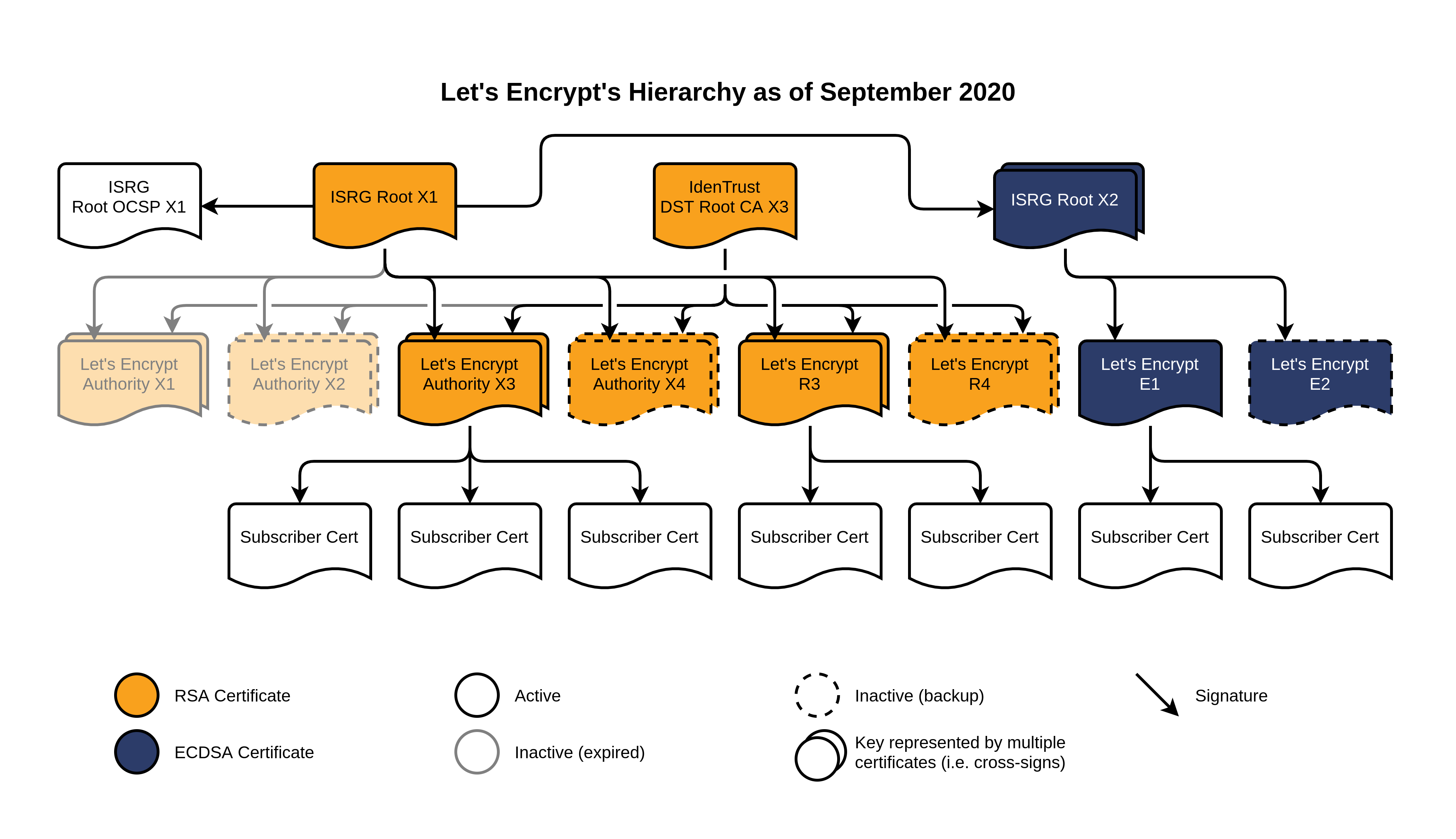

For starters, we’ve issued two new 2048-bit RSA intermediates which we’re calling R3 and R4. These are both issued by ISRG Root X1, and have 5-year lifetimes. They will also be cross-signed by IdenTrust. They’re basically direct replacements for our current X3 and X4, which are expiring in a year. We expect to switch our primary issuance pipeline to use R3 later this year, which won’t have any real effect on issuance or renewal.

The other new certificates are more interesting. First up, we have the new ISRG Root X2, which has an ECDSA P-384 key instead of RSA, and is valid until 2040. Issued from that, we have two new intermediates, E1 and E2, which are both also ECDSA and are valid for 5 years.

Notably, these ECDSA intermediates are not cross-signed by IdenTrust’s DST Root CA X3. Instead, the ISRG Root X2 itself is cross-signed by our existing ISRG Root X1. An astute observer might also notice that we have not issued an OCSP Signing Certificate from ISRG Root X2.

Now that we have the technical details out of the way, let’s dive in to why the new hierarchy looks the way it does.

Why We Issued an ECDSA Root and Intermediates

There are lots of other articles you can read about the benefits of ECDSA (smaller key sizes for the same level of security; correspondingly faster encryption, decryption, signing, and verification operations; and more). But for us, the big benefit comes from their smaller certificate sizes.

Every connection to a remote domain over https:// requires a TLS handshake. Every TLS handshake requires that the server provide its certificate. Validating that certificate requires a certificate chain (the list of all intermediates up to but not including a trusted root), which is also usually provided by the server. This means that every connection – and a page covered in ads and tracking pixels might have dozens or hundreds – ends up transmitting a large amount of certificate data. And every certificate contains both its own public key and a signature provided by its issuer.

While a 2048-bit RSA public key is about 256 bytes long, an ECDSA P-384 public key is only about 48 bytes. Similarly, the RSA signature will be another 256 bytes, while the ECDSA signature will only be 96 bytes. Factoring in some additional overhead, that’s a savings of nearly 400 bytes per certificate. Multiply that by how many certificates are in your chain, and how many connections you get in a day, and the bandwidth savings add up fast.

These savings are a public benefit both for our subscribers – who can be sites for which bandwidth can be a meaningful cost every month – and for end-users, who may have limited or metered connections. Bringing privacy to the whole Web doesn’t just mean making certificates available, it means making them efficient, too.

As an aside: since we’re concerned about certificate sizes, we’ve also taken a few other measures to save bytes in our new certificates. We’ve shortened their Subject Common Names from “Let’s Encrypt Authority X3” to just “R3”, relying on the previously-redundant Organization Name field to supply the words “Let’s Encrypt”. We’ve shortened their Authority Information Access Issuer and CRL Distribution Point URLs, and we’ve dropped their CPS and OCSP urls entirely. All of this adds up to another approximately 120 bytes of savings without making any substantive change to the useful information in the certificate.

Why We Cross-Signed the ECDSA Root

Cross-signing is an important step, bridging the gap between when a new root certificate is issued and when that root is incorporated into various trust stores. We know that it is going to take 5 years or so for our new ISRG Root X2 to be widely trusted itself, so in order for certificates issued by the E1 intermediate to be trusted, there needs to be a cross-sign somewhere in the chain.

We had basically two options: we could cross-sign the new ISRG Root X2 from our existing ISRG Root X1, or we could cross-sign the new E1 and E2 intermediates from ISRG Root X1. Let’s examine the pros and cons of each.

Cross-signing the new ISRG Root X2 certificate means that, if a user has ISRG Root X2 in their trust store, then their full certificate chain will be 100% ECDSA, giving them fast validation, as discussed above. And over the next few years, as ISRG Root X2 is incorporated into more and more trust stores, validation of ECDSA end-entity certificates will get faster without users or websites having to change anything. The tradeoff though is that, as long as X2 isn’t in trust stores, user agents will have to validate a chain with two intermediates: both E1 and X2 chaining up to the X1 root. This takes more time during certificate validation.

Cross-signing the intermediates directly has the opposite tradeoff. On the one hand, all of our chains will be the same length, with just one intermediate between the subscriber certificate and the widely-trusted ISRG Root X1. But on the other hand, when the ISRG Root X2 does become widely trusted, we’d have to go through another chain switch in order for anyone to gain the benefits of an all-ECDSA chain.

In the end, we decided that providing the option of all-ECDSA chains was more important, and so opted to go with the first option, and cross-sign the ISRG Root X2 itself.

Why We Didn’t Issue an OCSP Responder

The Online Certificate Status Protocol is a way for user agents to discover, in real time, whether or not a certificate they’re validating has been revoked. Whenever a browser wants to know if a certificate is still valid, it can simply hit a URL contained within the certificate itself and get a yes or no response, which is signed by another certificate and can be similarly validated. This is great for end-entity certificates, because the responses are small and fast, and any given user might care about (and therefore have to fetch) the validity of wildly different sets of certificates, depending on what sites they visit.

But intermediate certificates are a tiny subset of all certificates in the wild, are generally well-known, and are rarely revoked. Because of this, it can be much more efficient to simply maintain a Certificate Revocation List (CRL) containing validity information for all well-known intermediates. Our intermediate certificates all contain a URL from which a browser can fetch their CRL, and in fact some browsers even aggregate these into their own CRLs which they distribute with each update. This means that checking the revocation status of intermediates doesn’t require an extra network round trip before you can load a site, resulting in a better experience for everyone.

In fact, a recent change (ballot SC31) to the Baseline Requirements, which govern CAs, has made it so intermediate certificates are no longer required to include an OCSP URL; they can now have their revocation status served solely by CRL. And as noted above, we have removed the OCSP URL from our new intermediates. As a result, we didn’t need to issue an OCSP responder signed by ISRG Root X2.

Putting It All Together

Now that we’ve shared our new certificates look the way they do, there’s one last thing we’d like to mention: how we actually went about issuing them.

The creation of new root and intermediate certificates is a big deal, since their contents are so regulated and their private keys have to be so carefully protected. So much so that the act of issuing new ones is called a “ceremony”. Let’s Encrypt believes strongly in automation, so we wanted our ceremony to require as little human involvement as possible.

Over the last few months we’ve built a ceremony tool which, given appropriate configuration, can produce all of the desired keys, certificates, and requests for cross-signs. We also built a demo of our ceremony, showing what our configuration files would be, and allowing anyone to run it themselves and examine the resulting output. Our SREs put together a replica network, complete with Hardware Security Modules, and practiced the ceremony multiple times to ensure it would work flawlessly. We shared this demo with our technical advisory board, our community, and various mailing lists, and in the process received valuable feedback that actually influenced some of the decisions we’ve talked about above! Finally, on September 3rd, our Executive Director met with SREs at a secure datacenter to execute the whole ceremony, and record it for future audits.

And now the ceremony is complete. We’ve updated our certificates page to include details about all of our new certificates, and are beginning the process of requesting that our new root be incorporated into various trust stores. We intend to begin issuing with our new intermediates over the coming weeks, and will post further announcements in our community forum when we do.

We hope that this has been an interesting and informative tour around our hierarchy, and we look forward to continuing to improve the internet one certificate at a time. We’d like to thank IdenTrust for their early and ongoing support of our vision to change security on the Web for the better.

We depend on contributions from our community of users and supporters in order to provide our services. If your company or organization would like to sponsor Let’s Encrypt please email us at sponsor@letsencrypt.org. We ask that you make an individual contribution if it is within your means.