Scaling Our Rate Limits to Prepare for a Billion Active Certificates

Let’s Encrypt protects a vast portion of the Web by providing TLS certificates to over 550 million websites—a figure that has grown by 42% in the last year alone. We currently issue over 340,000 certificates per hour. To manage this immense traffic and maintain responsiveness under high demand, our infrastructure relies on rate limiting. In 2015, we introduced our first rate limiting system, built on MariaDB. It evolved alongside our rapidly growing service but eventually revealed its limits: straining database servers, forcing long reset times on subscribers, and slowing down every request.

We needed a solution built for the future—one that could scale with demand, reduce the load on MariaDB, and adapt to real-world subscriber request patterns. The result was a new rate limiting system powered by Redis and a proven virtual scheduling algorithm from the mid-90s. Efficient and scalable, and capable of handling over a billion active certificates.

Rate Limiting a Free Service is Hard

In 2015, Let’s Encrypt was in early preview, and we faced a unique challenge. We were poised to become incredibly popular, offering certificates freely and without requiring contact information or email verification. Ensuring fair usage and preventing abuse without traditional safeguards demanded an atypical approach to rate limiting.

We decided to limit the number of certificates issued—per week—for each registered domain. Registered domains are a limited resource with real costs, making them a natural and effective basis for rate limiting—one that mirrors the structure of the Web itself. Specifically, this approach targets the effective Top-Level Domain (eTLD), as defined by the Public Suffix List (PSL), plus one additional label to the left. For example, in new.blog.example.co.uk, the eTLD is .co.uk, making example.co.uk the eTLD+1.

Counting Events Was Easy

For each successfully issued certificate, we logged an entry in a table that recorded the registered domain, the issuance date, and other relevant details. To enforce rate limits, the system scanned this table, counted the rows matching a given registered domain within a specific time window, and compared the total to a configured threshold. This simple design formed the basis for all future rate limits.

Counting a Lot of Events Got Expensive

By 2019, we had added six new rate limits to protect our infrastructure as demand for certificates surged. Enforcing these limits required frequent scans of database tables to count recent matching events. These operations, especially on our heavily-used authorizations table, caused significant overhead, with reads outpacing all other tables—often by an order of magnitude.

Rate limit calculations were performed early in request processing and often. Counting rows in MariaDB, particularly for accounts with rate limit overrides, was inherently expensive and quickly became a scaling bottleneck.

Adding new limits required careful trade-offs. Decisions about whether to reuse existing schema, optimize indexes, or design purpose-built tables helped balance performance, complexity, and long-term maintainability.

Buying Runway — Offloading Reads

In late 2021, we updated our control plane and Boulder—our in-house CA software—to route most API reads, including rate limit checks, to database replicas. This reduced the load on the primary database and improved its overall health. At the same time, however, latency of rate limit checks during peak hours continued to rise, highlighting the limitations of scaling reads alone.

Sliding Windows Got Frustrating

Subscribers were frequently hitting rate limits unexpectedly, leaving them unable to request certificates for days. This issue stemmed from our use of relatively large rate limiting windows—most spanning a week. Subscribers could deplete their entire limit in just a few moments by repeating the same request, and find themselves locked out for the remainder of the week. This approach was inflexible and disruptive, causing unnecessary frustration and delays.

In early 2022, we patched the Duplicate Certificate limit to address this rigidity. Using a naive token-bucket approach, we allowed users to “earn back” requests incrementally, cutting the wait time—once rate limited—to about 1.4 days. The patch worked by fetching recent issuance timestamps and calculating the time between them to grant requests based on the time waited. This change also allowed us to include a Retry-After timestamp in rate limited responses. While this improved the user experience for this one limit, we understood it to be a temporary fix for a system in need of a larger overhaul.

When a Problem Grows Large Enough, It Finds the Time for You

Setting aside time for a complete overhaul of our rate-limiting system wasn’t easy. Our development team, composed of just three permanent engineers, typically juggles several competing priorities. Yet by 2023, our flagging rate limits code had begun to endanger the reliability of our MariaDB databases.

Our authorizations table was now regularly read an order of magnitude more than any other. Individually identifying and deleting unnecessary rows—or specific values—had proved unworkable due to poor MariaDB delete performance. Storage engines like InnoDB must maintain indexes, foreign key constraints, and transaction logs for every deletion, which significantly increases overhead for concurrent transactions and leads to gruelingly slow deletes.

Our SRE team automated the cleanup of old rows for many tables using the PARTITION command, which worked well for bookkeeping and compliance data. Unfortunately, we couldn’t apply it to most of our purpose-built rate limit tables. These tables depend on ON DUPLICATE KEY UPDATE, a mechanism that requires the targeted column to be a unique index or primary key, while partitioning demands that the primary key be included in the partitioning key.

Indexes on these tables—such as those tracking requested hostnames—often grew larger than the tables themselves and, in some cases, exceeded the memory of our smaller staging environment databases, eventually forcing us to periodically wipe them entirely.

By late 2023, this cascading confluence of complexities required a reckoning. We set out to design a rate limiting system built for the future.

The Solution: Redis + GCRA

We designed a system from the ground up that combines Redis for storage and the Generic Cell Rate Algorithm (GCRA) for managing request flow.

Why Redis?

Our engineers were already familiar with Redis, having recently deployed it to cache and serve OCSP responses. Its high throughput and low latency made it a candidate for tracking rate limit state as well.

By moving this data from MariaDB to Redis, we could eliminate the need for ever-expanding, purpose-built tables and indexes, significantly reducing read and write pressure. Redis’s feature set made it a perfect fit for the task. Most rate limit data is ephemeral—after a few days, or sometimes just minutes, it becomes irrelevant unless the subscriber calls us again. Redis’s per-key Time-To-Live would allow us to expire this data the moment it was no longer needed.

Redis also supports atomic integer operations, enabling fast, reliable counter updates, even when increments occur concurrently. Its “set if not exist” functionality ensures efficient initialization of keys, while pipeline support allows us to get and set multiple keys in bulk. This combination of familiarity, speed, simplicity, and flexibility made Redis the natural choice.

Why GCRA?

The Generic Cell Rate Algorithm (GCRA) is a virtual scheduling algorithm originally designed for telecommunication networks to regulate traffic and prevent congestion. Unlike traditional sliding window approaches that work in fixed time blocks, GCRA enforces rate limits continuously, making it well-suited to our goals.

A rate limit in GCRA is defined by two parameters: the emission interval and the burst tolerance. The emission interval specifies the minimum time that must pass between consecutive requests to maintain a steady rate. For example, an emission interval of one second allows one request per second on average. The burst tolerance determines how much unused capacity can be drawn on to allow short bursts of requests beyond the steady rate.

When a request is received, GCRA compares the current time to the Theoretical Arrival Time (TAT), which indicates when the next request is allowed under the steady rate. If the current time is greater than or equal to the TAT, the request is permitted, and the TAT is updated by adding the emission interval. If the current time plus the burst tolerance is greater than or equal to the TAT, the request is also permitted. In this case, the TAT is updated by adding the emission interval, reducing the remaining burst capacity.

However, if the current time plus the burst tolerance is less than the TAT, the request exceeds the rate limit and is denied. Conveniently, the difference between the TAT and the current time can then be returned to the subscriber in a Retry-After header, informing their client exactly how long to wait before trying again.

To illustrate, consider a rate limit of one request per second (emission interval = 1s) with a burst tolerance of three requests. Up to three requests can arrive back-to-back, but subsequent requests will be delayed until “now” catches up to the TAT, ensuring that the average rate over time remains one request per second.

What sets GCRA apart is its ability to automatically refill capacity gradually and continuously. Unlike sliding windows, where users must wait for an entire time block to reset, GCRA allows users to retry as soon as enough time has passed to maintain the steady rate. This dynamic pacing reduces frustration and provides a smoother, more predictable experience for subscribers.

GCRA is also storage and computationally efficient. It requires tracking only the TAT—stored as a single Unix timestamp—and performing simple arithmetic to enforce limits. This lightweight design allows it to scale to handle billions of requests, with minimal computational and memory overhead.

The Results: Faster, Smoother, and More Scalable

The transition to Redis and GCRA brought immediate, measurable improvements. We cut database load, improved response times, and delivered consistent performance even during periods of peak traffic. Subscribers now experience smoother, more predictable behavior, while the system’s increased permissiveness allows for certificates that the previous approach would have delayed—all achieved without sacrificing scalability or fairness.

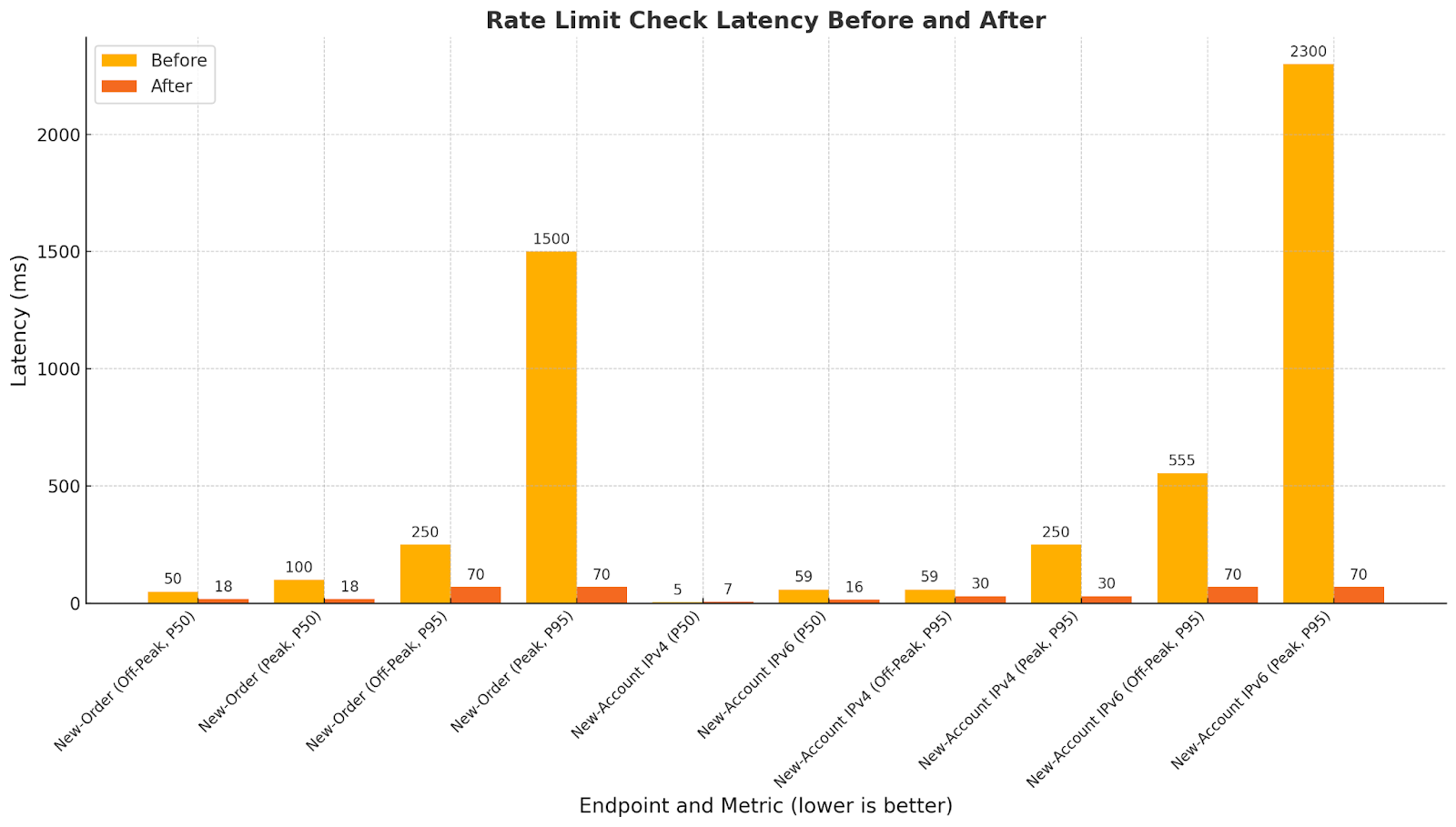

Rate Limit Check Latency

Check latency is the extra time added to each request while verifying rate limit compliance. Under the old MariaDB-based system, these checks slowed noticeably during peak traffic, when database contention caused significant delays. Our new Redis-based system dramatically reduced this overhead. The high-traffic “new-order” endpoint saw the greatest improvement, while the “new-account” endpoint—though considerably lighter in traffic—also benefited, especially callers with IPv6 addresses. These results show that our subscribers now experience consistent response times, even under peak load.

Database Health

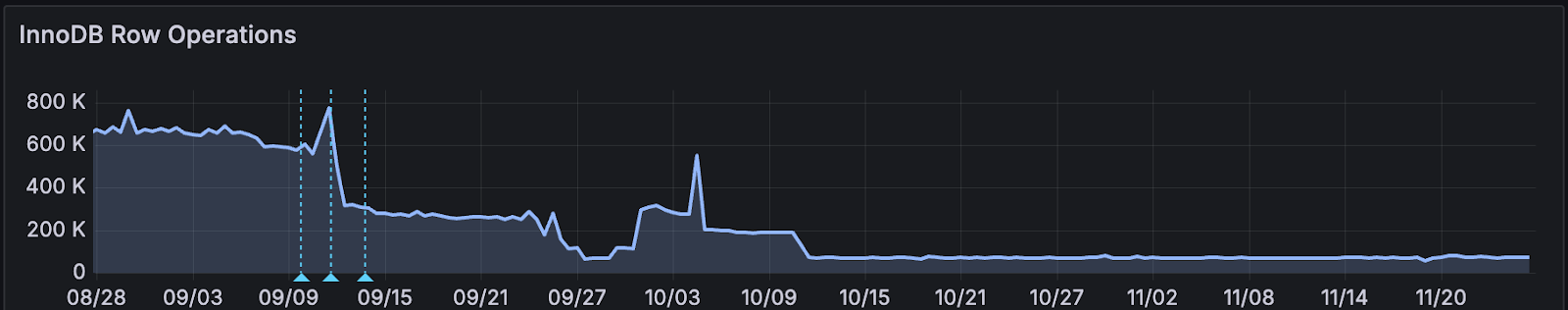

Our once strained database servers are now operating with ample headroom. In total, MariaDB operations have dropped by 80%, improving responsiveness, reducing contention, and freeing up resources for mission-critical issuance workflows.

Buffer pool requests have decreased by more than 50%, improving caching efficiency and reducing overall memory pressure.

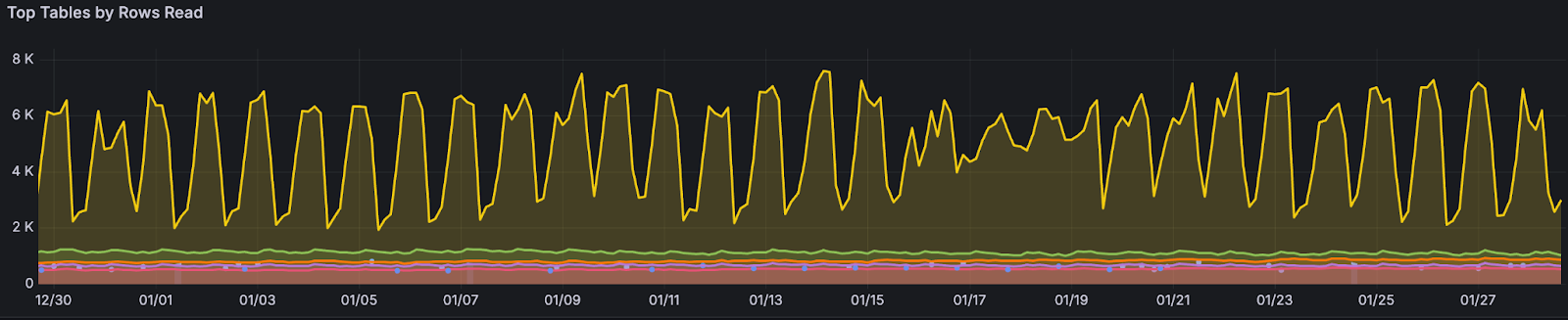

Reads of the authorizations table—a notorious bottleneck—have dropped by over 99%. Previously, this table outpaced all others by more than two orders of magnitude; now it ranks second (the green line below), just narrowly surpassing our third most-read table.

Tracking Zombie Clients

In late 2024, we turned our new rate limiting system toward a longstanding challenge: “zombie clients.” These requesters repeatedly attempt to issue certificates but fail, often because of expired domains or misconfigured DNS records. Together, they generate nearly half of all order attempts yet almost never succeed. We were able to build on this new infrastructure to record consecutive ACME challenge failures by account/domain pair and automatically “pause” this problematic issuance. The result has been a considerable reduction in resource consumption, freeing database and network capacity without disrupting legitimate traffic.

Scalability on Redis

Before deploying the limits to track zombie clients, we maintained just over 12.6 million unique TATs across several Redis databases. Within 24 hours, that number more than doubled to 26 million, and by the end of the week, it peaked at over 30 million. Yet, even with this sharp increase, there was no noticeable impact on rate limit responsiveness. That’s all we’ll share for now about zombie clients—there’s plenty more to unpack, but we’ll save those insights and figures for a future blog post.

What’s Next?

Scaling our rate limits to keep pace with the growth of the Web is a huge achievement, but there’s still more to do. In the near term, many of our other ACME endpoints rely on load balancers to enforce per-IP limits, which works but gives us little control over the feedback provided to subscribers. We’re looking to deploy this new infrastructure across those endpoints as well. Looking further ahead, we’re exploring how we might redefine our rate limits now that we’re no longer constrained by a system that simply counts events between two points in time.

By adopting Redis and GCRA, we’ve built a flexible, efficient rate limit system that promotes fair usage and enables our infrastructure to handle ever-growing demand. We’ll keep adapting to the ever-evolving Web while honoring our primary goal: giving people the certificates they need, for free, in the most user-friendly way we can.